Woman You Are Wine

Hello, Wine! Welcome to the Vineyard. Welcome to this setting of poetic reality.

Welcome Home!

The story of wine is the story of soul. Thus, wine-making is soul-making.

—Christina Forbes-Thomas

Christina Forbes-Thomas | Mythmaker

Hi there! I’m Chris. By now, it should be no secret about my passionate devotion to the fantasy image of wine.

Yes, there is wine's sensuous appeal, the excitement and glorious satisfaction when its starry splendour moves upon the palate. But when I speak of wine, I invoke its mythic depths, its ideological essence, its invigorating soulfulness—the history, symbolism, rituals and cross-cultural parallels, its regal truth and beauty, and its capacity for increasing life as a catalyst for spiritual ecstasy and transformation.

Wine is the image I am called to tend; it is the myth that chose me. But more on that later, trusting you’ll stick around and join our amazing circle. My background is in Depth Psychology with a specialization in Jungian and Archetypal studies. Woman you are Wine is my life’s work and personal myth, one in service of this image of wine—this evocative myth—and thus in service of humanity and wholeness. It is all spilled out here, in this sacred space. I’ve prepared a little tasting, so take a sip on Woman you are Wine as you walk through, and let it sit with you for a while:

Before a garden, a vine or grape existed in this world, our souls were intoxicated with immortal wine.”—Rumi

WOMAN YOU ARE WINE is a mythic expression of a woman’s course of consciousness, a Poetic art, practice and program, ritual container, and mentorship platform. Here, we engage the imagination, and adventure into images, symbols, myths, stories, and rituals that offer themselves up from the deep, abundant, and mysterious psyche.

WOMAN YOU ARE WINE is about love, psychological faith, truth, creativity, archetypal grace, maturation and care of the soul, and the development of your most instinctual qualities—the qualities that make you beautiful. Woman you are Wine’s distinct experience of a spiritual and psychological journey moves toward approaching, encountering and engaging the sacred through direct experience.

WOMAN YOU ARE WINE practices the art of Soul-making, which psychologist James Hillman describes delightfully:

“The work of soul-making is concerned essentially with the evocation of psychological faith, the faith arising from the psyche which shows as faith in the reality of the soul… Psychological faith begins in the love of images, and it flows mainly through the shapes of persons in reveries, fantasies, reflections, and imaginations. Their increasing vivification gives one an increasing conviction of having, and then of being, an interior reality of deep significance transcending one’s personal life.” (Re-Visioning Psychology, p. 50)

WOMAN YOU ARE WINE recognizes the sovereignty of each soul, cares for and is committed to the individual and the well-being of the culture. It gathers knowledge for fertilizing meaning from the fields of psychology, mythology, spirituality and wisdom traditions, ecology, the arts, and more. These pillars act as trellises that substantiate, support, sustain, and bring centeredness to the vines and veins of our lived experience.

“Call the world if you please “The Vale of Soul-making.”—John Keats

If you are led here, then my guess is that you have a sense of this longing we feel at the depths of our being. There is an urgency in your desire to connect, to create, to belong, to be in touch with this something we feel is greater than us, that stirs our fantasies, that furnishes our dreams, that guides our purpose. We call it by many names—the sacred, the divine essence, the beloved, fate, the numinous.

Our life is a continual process of artistic creation, and this process is a portal to accessing the sacred. It is an enactment of poetic faith. Avenues of access might be through imagination, dreams, stories, rituals, reflection, writing, gardening, and other such creative practices.

You’ll encounter very soon that my approach or the attitude I bring toward this work is less about “treating” and more about tending. It is about understanding and bringing into relationship, solidifying our interconnectedness and belonging with all living things—plants and animals, people, places, buildings, processes—as we experience ourselves as members of this grand whole. For myself and those I engage, this work is a creative activity. It is life in process, and we learn to dance with its rhythms and move with its tides. We gather and welcome all in this experience—joy, sorrow, relief, pain, love, disdain, hope, disappointments, inspiration—everything belongs.

Here, I joy to support you through two primary modes—Discovering and Myth & Memory-making:

Discovering: We often view our experience as something so personal, peculiar, only to us. This is not to discount your story. It does not mean that you and your situation are not special. But it might be bigger than that, in that, you are a part of a larger drama. And this approach of seeing, this perspective, might help you realize that you are not alone. It is that this idea, rather than discount, validates deeply your individual experience.

And so, this first mode of supporting you is in discovering the image or story that is at work in your experience. Perhaps it is the myth that you are living through, enacting, participating in—that natural transformational process that is happening. It is the story lurking in the background. Identifying this opens you up to your authenticity. This mythic-genealogical connection might help to get you through a difficult transition, a situation or to explore ways to reignite your passion for creativity, to reawaken the creative possibilities—the dominants in your depths. It could also be about insighting new or sustaining direction on the trajectory of your life.

Myth & Memory-making: Secondly, I offer support to help you create, own, and solidify your personal myth. In short, we are crafting and piecing together the patterns, peculiarities, and memories of your soulful experience. Here, through relational involvement and establishing a container, I aid you to engender soul.

Within these two modes is that awareness, too, that a part of soul-making is soul-destroying. It is not all building up and putting together. Some things must fall apart and break down. That is a crucial part of the work. And so it is here, in this sacred space you create, I hope you will love, live, and find life—anew.

Mentoring at WOMAN YOU ARE WINE engages you to:

- Be more conscious of your attitude in engaging your experiences

- Participate in a soulful inquiry of the authentic images that well up from your depths

- Explore how the divine makes itself known to you, to us.

- Develop a mythic sensibility to enrich your journey

Your soulful adventure is underway! As the Sufi scholar and poet Rumi says:

“What you seek is seeking you.”

VLOG

“I do nothing other than urge young and old to care not just for their persons and property,

but more so for the well-being of their souls.” – Socrates

The archived series of The Becoming Wives Show, an arm of WOMAN YOU ARE WINE

The Risen One: On Re-cognizing the Transformed Value

Author: Christina Forbes-Thomas

January 12, 2022

Individuation, a process of psychic development, as C.G. Jung saw it, is about fulfilling the potential of what one already is and was always meant to be. This paper sustains this perspective and, through the Jungian analysis, will illuminate the archetypal themes of death-rebirth and the archetype of transformation as it explores these dynamics in the alchemical original art of Woman You are Wine. Woman You are Wine is a psychotherapeutic container for the transformation of women as they course through the processes of death and rebirth in their lives. The discourse follows the mythic journey of wine, the domain of women, the awakening, differentiation, and homing of consciousness—and offers evidence of the symbolic landmarks of the Self and its function, interpenetrating every stage of transformation.

Archetypes and their Symbols

Contributing a cogent description of the character of archetypes, Eenwyk (1997) notes, “like magnets whose fields are invisible until they take shape in a substance that reveals their character, archetypes arrange psychic energy into patterns through which their character becomes discernable” (pp. 28-29). Archetypes then might be explored as containers of experience that shape, colour, and structure. They are multi-dimensional elements, with possessive charges affecting both psychic and external realms. The archetypes fulfill themselves through their vast medium of expressions and are comprised of both form and energy, linking different qualities such as body and spirit.

Archetype of Transformation

As an archetype that deals with change and transition and fosters the tension of opposites—death and life, dark and light—Jung (1959/1969), giving a more expressive elucidation of this symbolic process shares, “but the process itself involves another class of archetypes which one could call the archetypes of transformation” (p. 38). Unlike the more familiar ones—Mother, Hero, Wise Old Man—Jung emphasized that this class of archetypes is not expressed in personified form. Rather, the archetype embodies itself in usual everyday situations, places, and natural ongoing processes that might include inner and outer expeditions, rites and rituals, and practices like alchemy that explored the idea of transmuting base substance into gold or higher values.

Archetype of Death-Rebirth

The motif of death-rebirth lives at the heart of the transformation experience. Acknowledging the psychic reality of this motif in varied realms of experience, Jung (1959/1969) asserted in his essay, “Concerning Rebirth” that all notions of rebirth “are founded on this fact. Nature herself demands a death and rebirth . . . there are natural transformation processes which simply happen to us, whether we like it or not, and whether we know it or not” (p. 130). In the latter part of this statement, beyond the personal, Jung’s comment could be moving to highlight the indirect ways in which we might be thrust into participation with this process happening outside of us. One example could be through ritual. Rebirth also encompasses the concept of renewal which may be experienced wholistically, involving a change in the nature of the individual or in specific areas of one’s experience.

The Creation of Consciousness

This experience illustrates the archetypal stages of development that consciousness undergoes. In the creation of consciousness, the archetype of the Self—the archetype of wholeness—dwells in a state of original unity, comprising the totality of the opposites, but remains unconscious. From this unconscious depth, the ego-consciousness emerges, differentiates, evolves, and through a series of often distressing stages, involving bringing contents into relation, makes a return to its original depths. Perry (2011) expresses this aptly in the life of an individual, placing importance on how attaining consciousness entails a process of recognition and reflection:

This drive toward individuation is apparently a spontaneous urge, not under the leadership of the ego, but of the archetypal movement in the unconscious, the non-ego, toward the fulfilment of the specific basic pattern of the individual, striving toward wholeness, totality, and the differentiation of the specific potentialities that are innately destined to form the particular personality in question. The unconscious is the matrix out of which these various qualities arise step by step toward differentiation in consciousness, which they approach first in symbolic guise until the ego learns to understand and incorporate them. (p. 45)

Woman You are Wine: An Overview

Woman You are Wine (WYAW) is a poetic formulation and mythic expression of a woman’s course of consciousness—or psychic development—the framework’s primary symbol being wine. The work’s 12 initiatory phases of soul, which find a parallel in and is modelled on the viticulture and winemaking processes include: vine; clearing and ploughing; planting; bud break; flowering; fruit set and veraison; harvest; crushing; fermentation; clarification; maturation and bottling; and pouring. These phases facilitate archetypal movement, carrying the soul’s energy. The three other supportive phases or differentiated components—liberatory, instinctual, and labyrinthine—forming a sacred quaternity, vessels to contain the experience of symbolic images, cycles, and opposites.

The WYAW model (See figure 1) is the primal ground, the maternal womb or birth-place, the water wheel, and a pattern of cosmic order. A sacred encircling, it is a type of mandala and perceivable expression of the Self. It is an ongoing, Self-realizing process. Everything belongs to this creative whole, all psychic elements are contained in it, arranged by it, emerge from it, and convoy towards it. This principle of interconnectedness and harmonious archetypal relationship is central as various archetypes, symbols, and processes dawn, dance, dwindle, and descend throughout the journey as the Self makes something of its a priori nature known to consciousness—as it unveils something of its totality.

Myth of the Vine

Woman You are Wine postulates in symbolic experience that the grape was already wine. Grape, as a form of expression, emerges from the life-giving sustaining substrate, wine, and develops toward its wholeness. In the cyclic process of viticulture and the archetypal movements of vinification that houses mysteries, transformations, and distinctive units of experience, the grape returns to that which it already was in the beginning, to that immanent divine substance. It returns to wine. The wine has always been there. In mythical paradox, the grape is made of it and is it. This turning back to itself makes way for another form of transformation to begin.

This perspective leads toward consciousness of, and thus toward the divinity, the sacredness inherent in women and their connection to nature. That is, in Woman You are Wine, embracing the wholistic approach toward the Self, Woman is explored as the divine-human personification of the grape-vine, wherein the perception of her Self encompasses the natural world—a rediscovery of herself in nature—and by extent her microcosmic nature, and the complex multiplicity of being. This meaningful rediscovery and embodiment of her essence parallel the mythic path of Persephone’s descent to Hades. She rises in re-cognition, a coming to terms with and renewed knowing of the aspects of her Self and realization toward the greater person of her living totality.

Scholars and writers alike, have expressed sentiments toward this pattern of ideas. Edinger (1984), in discussing the primordial psyche and transformation, cites a midrash text of the “wine that was preserved in its grapes since the six days of creation” (p. 111). Rumi, narrating the essence of one’s being, declared in poetry, “the grapes of my body can only become wine” (as cited in Harvey, 2000, p. 28). In describing the process of individuation, Jacobi (1959) writes, “just as from the outset every seed contains the mature fruit as its hidden goal, so the human psyche, whether aware of it or not, resisting or unresisting, is oriented toward its 'wholeness'” (p.115). WYAW’s narrative might be perceived as an extension of Jacobi’s conception, that in such a case, there is an even deeper hidden goal. Here, we find that it is this living substance of the fruit that is the imago, the fully developed stage, the image that symbolizes its wholeness.

Even more compelling is mythologist Joseph Campbell’s commentary on a fresco painting (See Figure 2) from the Greco-Roman era of the god Bacchus (Dionysus) standing as “deified grape” next to Mount Vesuvius. The impressive image does not fail in its charge to induce insights into its relevance to consciousness and the dynamic relationship to soma. In his book, The Mythic Image, Campbell (1981) registers a major study of mythology across civilizations. On the artwork, he offers:

Here Dionysus appears in the character of the deified grape—not, however, as in the Christian doctrine of transubstantiation, brought down from above, from “out there” changing the “natural substance” of the grape into the altogether different “divine substance” of a god; but showing forth, in the way rather of a transfiguration, the immanent divinity that had been there in the grape all along. (p. 249)

Famed as “Mystagogue of rebirth” the twice-born god, one dismembered and returned to life, and a key figure in WYAW, has found favour in many writers. Kerènyi (1976) cites an orphic poem offering, "the last of Dionysus was wine, and the author of the poem calls the god himself ‘Oinos,’ ‘wine’” (pp. 249, 270.) Dionysus, in the same fashion later assured this resurrection to his cult as highlighted by Houser (1979). Otto (1965) elevates him to the foreground as the mad ecstasy who maintains intimate presence and participation in events at the time of birth and death, and that these wild forces—life and death—lie within the deity himself. Renowned for his frenzied rites, the process of transformation remains animated in every vine and terroir of life.

Shatter

In the vineyard, it is the flowers that create the lovely cluster of grapes. As one of the most crucial phases of pollination and fertilizing—an understandably apprehensive phase for vine growers—flowering determines the kind of vintage. Just enough of any kind of disruption to this delicate process—often weather factors—and it is a less-than-desired yield and vintage. Only fertilized flowers will grow into berries, but many flowers do not make it and fall off—a concept termed shatter. In WYAW, the concept, while considering outer domains of trauma, emphasizes the possibilities of the inner experience of shattering through the psyche’s self-defence system—as it seeks to keep the ego safe from certain changes and any attempts for expansion beyond the borders of certainty. This is furthered through one’s capacity to bear the contents arising from the unconscious. Le Grice (2021) endorses Jung’s view that, in individuation, one “becomes what one is, what one always was in potential” (p. 79). He maintained, regarding participation in the process that, in the course of development, one can be destroyed by or transform it into meaningful experiences.

This elaboration parallels the experience in viticulture and WYAW in exploring unconscious content. It considers the ability to “transform instinct into feeling and image” (p. 81). The capacity to contain the fantasies and constellated unconscious products, elevate them to a state of consciousness, and synthesize them through recognition is a crucial task to guard against this premature destruction. In his autobiography, Jung (1963) contended that many were broken by these experiences stating, “my enduring these storms was a question of brute strength. Others have been shattered by them—Nietzsche, and Hölderlin, and many others” (p. 177).

Bear

Jung’s description of his ability to endure evokes the concept of bear. To bear carries a morefold essence. This ability to produce, to yield—also manifold in meaning—to germinate, is activated in the soul’s process when a new symbol is needed. This is occasioned by the other aspect, the ability to hold the tension of opposites, synthesize, and act in a role as a carrier of transformation. It is the capacity to expand the imagination to facilitate, to bear and express something of one’s wholeness. It involves allowing room for the unconscious to respond. It may be visualized as the ego’s conflicting struggle with the tensions within, the suspension of the will, or Christ on the cross, as Jung identified. It can be conceived in the hanging fruit on the vine or the crushing darkness that haunts suffering and sacrifice. In redemptive fashion, this disruption, suffering, and psychic destruction, necessitating a reclamation of all aspects of one’s self, is experienced throughout the WYAW process and is a crucial agent of transformation and rebirth.

Sur Lie

In winemaking, a wine aged on the lees is kept in contact with the dead yeast cells which, in turn, alter the wine’s flavour, and improves its body—giving it a rich, creamy consistency. Lees will be carefully stirred up in the wine occasionally to receive this result through a technique called bâtonnage. Correspondingly, in WYAW, Sur Lie is conceived as a process of reintegrating, a restoration and revaluing of the bodily, and our sense of the sacred. It is the invitation and reclamation of the dregs of experiences, shadow elements—things that have been denied, rejected, repressed, left out—to bring depth, dimension, certainty, and balance to our experience. To make it our own and our own making it back into life, into the world is facilitated by psychological bâtonnage. It is a process of our recovery by nature, by the psyche. Within this, too, are memories, dreams, potentials, archetypal elements, and ancestral material. Wine is represented here as a historical symbol yet one that finds life and resonance in contemporary experience and convey to us something about ourselves, our souls, and our journey of transformation. Jung (1935/1966) stated:

Observe the sporadic emergence, whether in the form of images or of feelings, of those dim representations which detach themselves in the darkness from the invisible realm of the unconscious and move as shadows before the inturned gaze. In this way, things repressed and forgotten come back again. This is a gain in itself, though often a painful one, for the inferior and even the worthless belongs to me as my shadow and gives me substance and mass. How can I be substantial without casting a shadow? I must have a dark side too if I am to be whole. (para. 134)

The sixteenth-century alchemist Gerhard Dorn described three stages of alchemical transformation, the three coniunctios: unio mentalis; reunion of soul, spirit and body; and union with the unus mundus. These stages illustrate the separation and reinhabitation at work in the experience of bâtonnage—the process ultimately needed for a woman’s reunion with her innermost resources. Jung (1956/1970) expounded on this. From the original wholeness, unio mentalis is essentially uniting with one’s own mind and unburdening oneself from everything exterior and from the world around. It is engaging and embracing one’s interiority, and the depths of the inner life. It is a stage that fosters liberation from outer conditions and a gathering and fortifying of inner energies.

In the second stage, the unio mentalis and spirit reunite with the body. This enables the spiritual position to be realized—brought into reality—to connect with the instinctual, to be embodied for wholeness. The third stage of the coniunctio involves bringing the multiplicity of mind-soul-spirit-soma into union with the world, the unus mundus, creating a full-bodied experience. It is all of what man is with all of what nature is together. This expresses the process of individuation that fosters a rhythmic movement backwards, forwards, and around—in and out of these phases, and, even a further symbolic prospect of an invitation to dance across boundaries of time and space.

Mythologically, Kerenyi (1998) conjured the provocative expression “dead matter” as he advocated for how mythology may be communicated in its true nature. This “dead matter” is precisely what lees are in winemaking, what the old stories and collective myths are—passed down through vintage years, place, and value systems—and what our dreams, fantasies, shadows, creative expressions, and other psychic and outer material may be perceived as in our experience. They are fertile dominants waiting to be brought into consciousness, connecting us to the greater history and story of the soul. Kerenyi suggests that to restore this thing to itself, what is required is “translating it back into its original medium” (p. 4), wherein it may be re-cognized—advanced into consciousness—participated with, gain life in our experience, and deeply rooted resonance.

Sharing Kerenyi’s perspective in viewing our lives archetypally, Jung contributed further, perhaps from a more psycho-religious approach. He speaks of the ever-recurring psychic motifs and cites the support of its universality and timelessness. Contending that Christ’s experience of the descent into hell and later rise in heaven parallels the disappearance of the value in the unconscious whereby it overcomes the dark powers and rises again in a new form, new sovereignty, Jung offers a remarkable elaboration on these principles:

God’s death, or his disappearance, is by no means only a Christian symbol. The search which follows the death is still repeated today after the death of a Dalai Lama, and in antiquity it was celebrated in the annual search for the Kore. Such a wide distribution argues in favour of the universal occurrence of this typical psychic process: the highest value, which gives life and meaning, has got lost. This is a typical experience that has been repeated many times, and its expression therefore occupies a central place in the Christian mystery. The death or loss must always repeat itself: Christ always dies, and always he is born; for the psychic life of the archetype is timeless in comparison with our individual time-boundness. According to what laws now one and now another aspect of the archetype enters into active manifestation, I do not know. I only know—and here I am expressing what countless other people know—that the present is a time of God’s death and disappearance. The myth says he was not to be found where his body was laid. 'Body' means the outward, visible form, the erstwhile but ephemeral setting for the highest value. The myth further says that the value rose again in a miraculous manner, transformed. It looks like a miracle, for, when a value disappears, it always seems to be lost irretrievably. So it is quite unexpected that it should come back." (Jung 1940/1969, pp. 89-90)

New Wine

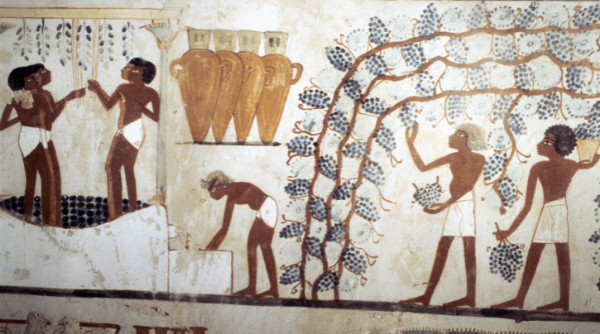

The risen one. The immortal. The transformed value. The divine essence. The realized feminine. It goes by many names and finds inestimable expressions. The dynamic ‘life-death-life’ process shares traits with the lifeforce of the grapevine in everyday existence. The motif runs on trellises from the cycles in nature to the ancient Egyptian tomb of Sennefer. Jung (1969/1959) in “Concerning Rebirth,” offers an arresting summary of the birth and development of consciousness, of the ego’s emergence and return to its original wholeness:

When a summit of life is reached, when the bud unfolds and from the

lesser the greater emerges, then, as Nietzsche says, ‘One becomes Two,’ and the greater figure, which one always was but which remained invisible, appears to the lesser personality with the force of a revelation. He who is truly and hopelessly little will always drag the revelation of the greater down to the level of his littleness, and will never understand that the day of judgment for his littleness has dawned. But the man who is inwardly great will know that the long expected friend of his soul, the immortal one, has now really come, ‘to lead captivity captive’; that is, to seize hold of him by whom this immortal had always been confined and held prisoner, and to make his life flow into that greater life—a moment of deadliest peril! (p. 121)

What we Carry

The young American inaugural poet-activist Amanda Gorman’s recently published book bears the educing title, Call Us What We Carry. What does Woman carry? The title is pregnant with psychic potentials. Through this symbolic passageway, this aged rite of transformation, she carries the subtleties of divine truth, archetypal potentials, and forms. The medium of her personhood sustains the unity of the larger realities of experience. She brings us into relationship with ourselves, our longings, our spiritual-historical roots. As vessel and bearer, she transports ideas, endeavours, numinosity, and historical consciousness that situate us onto all grounds of existence and that is vital for the times. In African cultures, there is a traditional mode of participation known as call-and-response, similarly expressed in music. In direct commentary to Gorman’s Call Us What We Carry—the author of this discourse responds, Woman, I call you Wine.

Even here as the image of mother and child is invoked, the archetype of transformation is expressed. It reflects the conception of consciousness and its differentiation from the unconscious, the womb from which consciousness emerges. It points to the work of consciousness to participate in gathering and fulfilling collective qualities toward the development of wholeness. Jung (1959/1969) in his essay on “The Psychology of the Child Archetype” comments, “the clearest and most significant manifestation of the child motif. . . is in the maturation process of personality induced by the analysis of the unconscious, which I have termed the process of individuation” (Para 159). Like the hermaphroditic grapevine that pollinates itself, the Mother contains all archetypal forms and opposites and unites them in herself, propelling us into the arduous journey.

What is also evident hither is a mythic confirmation of Woman You are Wine’s “Myth of the Vine” earlier elucidated—that the grape was always wine. Wine in its wholeness is archetypal Mother, and grape, Child spirit. This grape-child-consciousness represents potentiality and wholeness as inherited from its origin and is manifested in all phases of soul throughout the Woman You are Wine framework, and hence throughout our lives in our efforts for growth and expansion. It likewise unveils the incestuous pattern of the Child returning to Mother, of the mythical union of consciousness turning back to the unconscious where the cycle of life and renewal continues. Jung (1959/1969) was discerning in his observation that “rebirth is an affirmation that must be counted among the primordial affirmations of mankind” (para. 116).

Pouring

In the words of poet Rainer Maria Rilke, we might find residues for reflection on how the Self employs and engages us to carry out its endeavour for completion, to manifest its wholeness that we, too, are intimately bound in. “What will you do, God, should I die? Should your cup break? That cup am I. I am the trade you carry on, With me is all your meaning gone” (Rilke, 1975, p. 01). Here, the point of the single unity is emphasized, that the sacred is in us, that we are in a relationship with the depths of the world, and that all is one cosmos.

The psychic task of pouring what she carries is soul in service of the Self, of the times, in fulfilment of wholeness. It is the restoration and flow of life energy. The needful action involves what Jung (1940/1969) describes as the need to take “thought-forms that have become historically fixed, try to melt them down again and pour them into moulds of immediate experience” (para 148). And here Plato (Republic, III,) might be invoked as well, when he states that “when a beautiful soul harmonizes with a beautiful form, and the two are cast in one mold, that will be the fairest of sights to him who has an eye to see it” (p. 402d). That is key in the pouring, a continuity as an expression of what the unconscious, the Self, and individuation are. It is always happening. It must always be happening in realizing completeness. It is the Self in its limitless creative expression and sacred transformative hospitality manifesting through us.

Conclusion

Using Jungian analysis to elucidate the archetypal themes of death-rebirth and transformation in the art of Woman You are Wine, this discourse performs the very nature of the task of transformation, and here, at its conclusion, returns to the call of the numinous totality where it began. It presents evidence to substantiate the existence of the aforementioned motifs in all realms of experience that ultimately belong together as one. Such a kind of living transformative art and symbolic formulation is proof that the agency of psyche continues at work finding new and creative ways to express itself—the Self—in contemporary experiences for the times, effecting the lives of modern man and woman.

References

Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism. (n.d.). Retrieved January 12, 2022, from http://aras.org.pgi.idm.oclc.org/records/bos.131

Campbell, J. (1981). The mythic image. Princeton.

Edinger, E. F. (1984). The creation of consciousness. Inner City Books.

Harvey, A. (2000). The way of passion: A celebration of Rumi. TarcherPerigee.

Houser, C. (1979). Dionysos and his circle: Ancient through modern. Harvard University.

Jacobi, J. (1959). Complex, archetype, symbol. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, dreams, reflections. Vintage.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Series Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 9, pt. I, 2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1959)

Jung, C. G. (1969). Psychology and religion. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In (H. Read et al., Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 11, pp. 3-105). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1940)

Jung, C. G. (1966). Problems of modern Psychotherapy (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). In H. Read et al. (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 16. Practice of psychotherapy (2nd ed., pp. 53-75). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1935)

Jung, C. G. (1970). Mysterium coniunctionis (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) In (H. Read et

al., Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 14). Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1956)

Kerenyi, C. (1998). The gods of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson.

Kerenyi, C. (1976). Dionysos:Archetypal image of indestructible life (Ralph Manheim, Trans.). BS LXV. 2 . Princeton University Press.

Le Grice, K. (2021). Archetypal reflections: Insights and ideas from Jungian psychology. ITAS Publications.

Otto, W. F. (1965). Dionysus. Indiana University Press.

Perry, J. W. (2011). The self in psychotic process. Literary Licensing.

Rilke, R. M. (2011). Poems from the book of hours. New Directions.

Samuels, A., Shorter, B. & Plaut, F. (1986). A critical dictionary of Jungian analysis (pp. 1-184). Routledge.

Van Eenwyk, J. R. (1997). Archetypes and strange attractors. Inner City Books.

CONTACT

Get in touch! Let’s explore how I can support your soul-making.

I offer a complimentary initial 20-minute consultation via Zoom or by phone. There are no commitments. Your soul will guide you.

Email your inquiries about consultation, mentorship, and more to: christina@womanyouarewine.com